The

Battle of Santa Cruz

Prelude Campaign and Battle

11th October to 26th October 1942

Prelude Campaign

The Battle for Henderson Field

With

Imperial Japanese Army troops still vainly struggling to subdue the beleaguered

U.S. Marines who stubbornly clung to the Henderson Field perimeter like

a drowning sailor to a preserver, Imperial General Headquarters was loath

to leave the situation alone. Strict measures and decisive action would

have to be taken to achieve the sort of overwhelming victory at Guadalcanal

that morale and strategy required to keep the possibility of final victory

open.

It was not surprising what

the collective minds of the Imperial General Headquarters at Tokyo, still

the top authority on the conduct of the war, and Combined Fleet with its

seagoing headquarters on the "Hotel Yamato” in

beautiful and peaceful Truk

lagoon, churned out for execution in the three final weeks of October,

1942.

Similar

in appearance to the operations that had led to the Battle of the Eastern

Solomons, but more extensive and carefully planned, their scheme offered

a foolproof method of eliminating any American opposition to Japanese reinforcement

runs to Guadalcanal – either by mere threat of force imposed on a weak

opponent, or by 0attacking and destroying him if he dared oppose the Imperial

Navy.

All operations

would be tied to the progress of the 17th Army on Guadalcanal. General

Kawaguchi, Commander-In-Chief, would set a time by which his forces would

be placed in such fashion as to overwhelm the Americans (who were still

considered rather weak in number and by comparison) and bring Henderson

Field into Japanese possession. The IJN, with a powerful five-carrier force,

would move forward to fall upon the U.S. Navy's flanks if it attempted

its own reinforcement runs, evacuation maneuvers, or even tried to employ

its carriers in a fleet battle.

The naval

operations that would provide Kawaguchi with the necessary additional ground

support – artillery pieces, supplies, and most importantly, more men --

would be conducted as two major reinforcement runs and repeated but regular

runs of the Tokyo Express.

When Admiral

Kondo, in charge of Combined Fleet operations, put to sea at 1330 on 11

October 1942, with two battleships and carriers Hiyo and Junyo,

trailing Nagumo's three-carrier 3rd Fleet by three and a half hours, the

first of these reinforcement runs was already being executed. It would

be an awkward opening for the IJN's most carefully planned campaign. This

first reinforcement run, a "singularly important” (-1-)

run by a reinforced Tokyo Express, containing seaplane carriers Nisshin

and Chitose, would lift heavy artillery, ammunition and men

to Guadalcanal, necessary ingredients to General Kawaguchi's recipe for

winning on the ground. Accompanying them would be 8th Fleet's CruDiv 6,

or better, its three remnants, under Rear-Admiral Goto Aritomo. Their laborious

task would be to shell and disable the feared Cactus Air Force and thus

open a route for easier reinforcement both day and night. Alas, it did

not turn out the way it was intended.

The Tokyo

Express, preceding Goto, arrived at Guadalcanal and successfully disembarked

its load. Goto, however, stumbled unprepared into Rear-Admiral Norman Scott

and was soundly defeated in the ensuing battle of Cape Esperance.

It was

a heavy blow to Japanese morale, and yet it happened to be only a partial

defeat within the global scope of the campaign; the most important part,

the safe delivery of Kawaguchi's highly needed reinforcements, was accomplished.

While

the Japanese reinforced, a small U.S. convoy under Rear-Admiral Richmond

Turner also approached Lunga Roads, carrying the National Guardsmen of

the 164th Regiment of the Americal Division to their first combat duty.

Crowded aboard two freighters were the 2,900 men of the regiment, plus

Marine replacements.

Turner

arrived off Lunga on 13 October and stumbled into the major air offensive

preparing for the IJN's second important convoy, this one not a Tokyo Express

but a genuine convoy. It was fortunate for Turner that the 11th Air Fleet

had not considered a strike at naval forces and chose to hit the runways

of Henderson Field instead.

This convoy, called the

"High Speed Convoy” by virtue of its comparatively fast movement, consisted

of six fast transports and an escort of eight destroyers, and carried 4,500

men and many rounds of ammunition, again vital to the 17th Army on Guadalcanal.

To box

this unit through, Combined Fleet had assigned it powerful support in the

form of two battleships, Kongo and Haruna, under the command

of Rear-Admiral Kurita Takeo, to bombard Henderson Field in the night before

the convoy's arrival. It was obvious that such a heavy shelling would incapacitate

U.S. air power on the island, and together with the carriers now within

supporting distance to the north, any threat to the convoy would be fought

off.

Kurita's arrival at Lunga

Roads in the first hours of 14 October was the first and last time that

Henderson Field would be subjected to a battleship bombardment; alas, that

took nothing away from the savageness of the action.

Kurita's sixteen 14” guns

loaded with Type 3 bombardment shells(-2-)

took to hitting Henderson Field for an hour and a half, and when Kurita

departed, most of the Cactus Air Force had been obliterated, along with

the greater part of its fuel reserves.

There

had been light casualties overall, but the command staff of VMSB-141 and

most of its planes had been destroyed, severely limiting Henderson Field's

striking power on the last day it could possibly intervene with the High

Speed Convoy's approach. Yamamoto hurried his forces south to engage a

now-coverless U.S. fleet and win the campaign. However, Yamamoto was a

bit over-ecstatic: Henderson, while severely hit, was in fighting spirits.

The Americans scraped together every flyable plane to hit back at the convoy,

which they did throughout the afternoon of 14 October. Their tireless efforts

did little to decelerate the convoy's advance, but it was a vital feeling

of doing something that would help efforts on the 15th. Imperial command

units were in high spirits. Their important convoy anchored off Tassafaronga

at midnight on the 14th, and commenced unloading immediately. A Tokyo Express

added another 1,100 men to the landed troops, and Admiral Mikawa dropped

another 700 8” shells within the Henderson Field perimeter, an effort which

meant little to the Marines after Kurita's shelling the previous night.

2nd Fleet's

carriers provided cover for the still-unloading convoy on the next morning,

but several relays of attackers, first piecemeal, then coordinated, hit

at the transports and forced three to beach themselves. One more transport

was completely unloaded and retired, but Admiral Takama, in charge of the

operation, abandoned the disembarkation and headed north of Savo, to maneuver

his ships more effectively -- and never returned when the night, under

a full moon, brought no relief from Henderson's constant attacks.

That night,

yet another 8” bombardment, this one by cruisers Myoko and Maya,

hit Henderson, but it neither turned the tide of operations. Henderson

remained more or less operable, although the amount of planes it housed

had considerably decreased.

On 16

October, the renewed aerial offensive cost the U.S. a destroyer, but finally,

the Americans were reasonably close to offering the Japanese resistance

at sea. Carrier Enterprise left the homely waters of the Hawaiian

Islands, where she had been receiving extensive if rushed repairs for the

past month, and headed south to reinforce the only carrier then available,

Hornet. With her Air Group 10, the U.S. might actually be in a position

to move against any further operations of the IJN. But while Enterprise

proceeded on her seven-day journey from Pearl Harbor to the Solomons,

the Japanese experienced further trouble. Though the reinforcements had

been landed largely as scheduled, an early-morning bombardment by destroyers

Aaron Ward and Lardner had laced the freshly stocked ammunition

dump near the debarkation area of the previous convoy; 2,000 5” shells

burst into the area and ignited the greater part of the vital stocks.

Accordingly,

General Kawaguchi was unable to conduct his attack as planned (difficulties

in moving his large forces also played into this decision), and he decided

to postpone his move from the 20th to the 22nd – a move which the Navy

only barely found out about.

The Imperial

Navy had problems of its own. With all its major forces deployed at sea,

fuel was getting critically low – so low that one of the supporting tankers

had to return to Truk and take aboard fuel from battleships Yamato and

Mutsu, for no other reserves were left at this advance base.

It was

on 18 October 1942 that the campaign took its most sharp turn for the Allies

when Admiral Nimitz, tired of Vice-Admiral Ghormley's (COMSOPAC) cautiousness

(some said, timidity) and obvious disorganisation, with the approval of

Admiral King relieved Ghormley and replaced him with Vice-Admiral William

F. "Bull” Halsey. It was Halsey's finest hour. A stocky, tough-looking

individual with a gritty face and personal manner that fit his nickname,

this former Naval Academy boxer and football player was preceded by his

reputation as a fiercely attack-minded fighter who cared little for formula

but much for performance. His mere presence lifted American spirits and

his first acts in office did likewise – he ordered neckties removed from

Navy uniforms and moved the headquarters from pleasant but remote Auckland

to the closer Nouméa.

The IJN,

meanwhile, paid another price for the continuous delays in the opening

of the ground campaign -- which had been postponed to the 24th -- when

Hiyo, one of 2nd Fleet's carriers, suffered an engine breakdown

on the 21st that could not be fixed at sea, forcing her to retire to Truk,

leaving behind several of her planes that were transferred to Junyo.

It so

came that 24 October would be the most important day for the Santa

Cruz campaign. That morning, the Japanese launched their offensive on Henderson

Field. In a battle lasting three days and nights, the Sendai Division hurled

itself into the southern side of the U.S. perimeter, while IJN forces moved

into support range to Guadalcanal's north, expecting the battle to be successful

and hoping for a crack at the elusive U.S. Navy forces.

Those

forces had met that same day some 850nm north of Guadalcanal. Hornet

and her consorts under Rear-Admiral George Murray, and Enterprise

with battleships South Dakota and her escorts under Rear-Admiral

Thomas Kinkaid rendezvoused, the largest assembly of naval power the U.S.

had in the Pacific and, but for Rear-Admiral Willis Lee's Washington

surface action group, the only.

With Kinkaid in charge of tactical maneuvering, the U.S. had an able leader,

but Enterprise lacked the elaborate fighter-direction offices of

her younger sister, making Kinkaid's decision to control every element

of the battle from the Big E a weak point in the plan.

In most other respects, as well, Kinkaid's position was less than enviable.

Though he possessed two powerful carriers, his total air strength was less

than the of the IJN, and his air crews, especially Enterprise’s

Air Group Ten, were not up to the abilities of their counterparts. The

confusion within the IJN's seagoing commands had not been helped by the

repeated delays in the 17th Army's advance. Admiral Nagumo, after the second

delay, and the second time he had to turn back out of his ongoing support

operations, refused to go south again by the same course, considering it

most likely that he would be detected early. From Truk came the stern reply

of Vice-Admiral Ugaki – continue according to plan. Nagumo would be forced

south whether he liked it or not.

And so,

when on the 24th the Army finally advanced to the attack, Nagumo and Kondo

took their units down their scheduled routes and sought out contact with

Kinkaid's weaker forces. The IJN was in high spirits and confident, and

a false report that Army forces had captured the airfield did not help

to leaven its anxiety to engage.

The Battle

25 -- 27 October 1942

It was

as Nagumo had predicted, however: just after noon on the 25th, one of the

ubiquitous PBY Catalina flying boats snooped on Nagumo, and reported him

back to Kinkaid and Halsey. From the latter, the very simple order went

out: "Attack, Repeat, Attack”. The Battle of Santa Cruz was about to start.

Though

Yamamoto was subsequently informed of the falsity of the Army's report

of the capture of Henderson Field, the IJN continued to go charging down

toward Guadalcanal. The IJN's disposition for this battle had considerably

changed from how it had fought the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. No longer

would surface forces sail behind the all-important carriers, waiting for

the decisive surface engagement. Yamamoto had arrayed his surface forces,

under Vice-Admirals Kondo and Abe, to take station some 60 miles ahead

and to the flanks of Admiral Nagumo Chuichi's vital carriers.

Their

task would be to draw search planes and attackers onto themselves, thus

preventing damage to the carriers. They would perform rather well in this

role. As both sides closed the prospective arena for their fight, both

sides had to cope with different problems. Nagumo had his carriers detected

at 0250 on the 26th, and the passing Catalina lost no time dropping a stick

of bombs behind Zuikaku. Nagumo turned hard and moved north, Abe

and Kondo corresponding to his moves. At 20 knots, the forces maintained

this course until their first rendezvous with the enemy. Admiral Kinkaid

had a strike group spotted on Hornet throughout the night in hopes

of making use of a Catalina report within the first hours of the new day,

but his hopes were not fulfilled. No contacts warm enough to warrant their

pursuit were left, and thus Kinkaid ordered Enterprise to launch

her own search-strike force, successive groups of two Dauntless dive bombers,

each lugging a 500-lb. bomb. Eleven such pairs were in the air by 0500

on the 26th, and their search would bear fruit soon. First, a pair detected

Admiral Abe's Vanguard Force, but at 0650, 200nm to the northwest of Kinkaid,

two Dauntlesses had located Nagumo's carriers and carefully noted their

position, speed and heading, before being chased off by Zeros. Kinkaid

received this report quickly enough. So did two other Dauntless dive bombers,

whose pilots made out Nagumo at 0740 and placed a bomb on the aft flight-deck

of light carrier Zuiho, putting her out of the action.

Kinkaid

ordered his planes to strike. From Hornet at 0730, twenty-nine planes

lifted off, followed by nineteen from Enterprise at 0800, and eventually

twenty-five more from Hornet at 0815. By the time these strikes

were in the air, however, Nagumo had already cast his dice.

His air

search, scout planes from cruisers and B5N Kate carrier attack planes from

Zuikaku, had succeeded in locating Kinkaid's barely separated carriers,

but although a sighting contact had been made by 0612, the aircrew did

not report this until 0658 and misidentified itself in the course of its

report; but although serious doubts were entertained by Nagumo and his

staff as to the quality of the report, they decided they could not ignore

it. At 0725, 62 planes from all three carriers of Nagumo's force had assembled

and were heading to the position indicated in the report of the scout.

Immediately, the three carriers

re-spotted their remaining planes, but Zuiho's unhappy experience

reduced the second wave to just Zuikaku's and Shokaku's planes

– a further 48 planes to add to the first strike.

It was

most unfortunate for the Americans that both Japanese and American aircraft

had to pass through the same space of air. A mere 60nm from its home, the

Enterprise strike was bounced by the incoming Japanese strike's

escorts and lost eight planes without being able to effect sufficient retribution.

The Americans informed their vessels; in both Hornet and Enterprise,

action was taken to brace the ship for damage. The Japanese came into radar

range not long after their struggle with Enterprise’s airstrike;

they headed for Hornet.

CAP hurried

to intercept them, but it was to little avail, since the Enterprise

Fighter Direction Officer completely failed to deliver effective information

to the fighters.

Hornet

and her escorts increased speed and tightened distances, and when dive

bombers were spotted overhead, Captain Mason started swinging his command

around. But although he was able to avoid a good part of the bombs launched

at him, three bombs smashed into his deck, and one more crashed into her

accompanied by its mother plane, testimony of the deadliness of Hornet's

defensive fire – as were the wrecks of another sixteen aircraft strewn

around the carrier. But the hits were severe, and the simultaneous attacks

by B5N Kates didn't help either. While two torpedoes smashed into her starboard

side, another D3A Val dive bomber crossed her deck diagonally and plowed

into the deck and forward elevator well.

Fifteen

minutes had transformed Hornet into a blazing wreck, motionlessly

sitting on the ocean with thick black smoke belching from her innards.

She had taken 38 of 52 Japanese with her; but her future looked exceedingly

bleak. Meanwhile, the Hornet attack group had, at 0918, detected

3rd Fleet's carrier force, distinctively marked by the smoking Zuiho,

but lacked power since its poorly organized strike had lost cohesion on

the flight. One Dauntless was brought down by defending Zeros, and two

quit their attack runs after damage, but the remaining eleven scored a

total of four bomb hits from stem to stern on the carrier, leaving her

badly aflame and out of the battle for good. Almost two years would pass

before she would ever launch offensive strikes again.

Nagumo,

now with two of his three carriers out of action and Zuikaku's air

group fully committed, retired to the north awaiting the results of his

strikes, while on the other side, Hornet's damage control crews

worked frantically to restore that carrier's fighting power.

Kinkaid

had knocked out two carriers for the price of one, though Enterprise’s

small strike had not found a flattop and had elected to strike elements

of the Vanguard Force, failing to damage anything. Hornet's second

strike had had no luck either, finding only the heavy cruiser Chikuma

and plastering her with four bombs, it left her in a moderately damaged

condition. In Enterprise, the day's actions had not spelled much

luck for the newly arrived carrier. A freak torpedo accident involving

a TBF torpedo released by the ditching plane caused heavy damage to destroyer

Porter, and Kinkaid ordered the destroyer sunk, expecting further

action and not wanting the complications of having his screen weakened.

The airborne ambush of her strike group was not a good luck sign either,

and now, at 1000, the greenish pips of airborne contacts appeared on the

screens in Enterprise’s radar compartment. Once more, her Fighter

Direction sprang into action, moving divisions of blue Wildcat fighters

around the sky to bounce the bogeys and save the invaluable flight deck

of America's last Pacific carrier, but their efforts were largely in vain.

Enterprise's

guns, including sixteen of the new and deadly 40mm Bofors, and those guns

of her escorts that could provide even the slightest aid in protecting

the flattop, were brought to bear on an as yet invisible enemy. Enterprise's

fire-control radar failed her; and it was the naked eyes of her topside

lookouts that caught the first glimpse of the shiny-gray dive bombers that

came hurtling through an empty sky devoid of anti-aircraft fire, at 1015.

Suddenly,

from the screen and Enterprise's gun galleries came the sudden burst

of gunfire that in carrier battles marked the beginning of swift action

with critically important results. AA cruiser San Juan and battleship

South Dakota seemed as if dyed in the red of fire and gray of smoke

as their powerful five-inch batteries opened up simultaneously. The continuous

rattling of 20mm and 40mm artillery added yellow tracers that pointed at

the incoming strike planes, and on her open bridge, Enterprise’s

Captain Osborne Hardison shouted the helmsmen steering orders for maneuvers

designed to fool the Imperial Navy's assault pilots. It was not until 1017

that the first bomb caught Enterprise on her flight deck's overhang

and exploded in the air off-board her port bow. Almost at the same instant,

another bomb penetrated near her forward elevator and blew up below, igniting

fires and wiping out a repair party. Another violent near-hit shook the

entire ship at 1019, wrecking the plating of two oil tanks and causing

the entire ship to flex up-and-downward for several seconds.

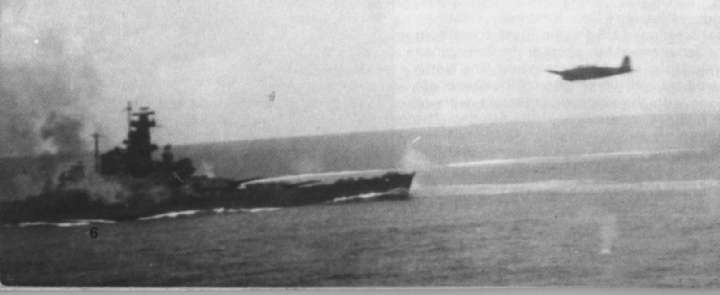

A Kate heading over South Dakota after having released

her torpedo.

A Kate heading over South Dakota after having released

her torpedo.

|

Enterprise

was in bad condition, but she had been spared the coordinated attacks

that had gotten Hornet. The B5N strike of torpedo planes followed

only twenty minutes later, first coming into sight at 1044. Captain Hardison

moved to comb the wakes of three launched torpedoes, then swerved around

his command to bring her out of the danger of hitting destroyer Shaw and

a fourth torpedo. More torpedo tracks were avoided, and when the last Kate

had pointed her spinner for home, Enterprise was steaming at 27

knots, South Dakota off her starboard quarter, having defiantly

withstood two separate attacks. |

However,

it was still to be decided who would see the end of this day. With just

Zuikaku of his force in fighting condition and her airgroup committed,

Nagumo would elect to turn command of the operation over to Rear-Admiral

Kakuta Kakuji aboard the carrier Junyo at 1140. Her 44-plane air unit had

not been committed when the attacks on Shokaku were delivered, and

subsequently at 0917, the aggressive Kakuta launched seventeen D3A Val

dive-bombers to attack Hornet, the only carrier a bearing was available

for, but later, the attack was pointed at Enterprise. It was 1121,

six minutes after the carrier had commenced landing her planes, that these

Vals hurtled from the skies above Enterprise, her Task Force steaming

towards the gray outlines of a squall ahead.

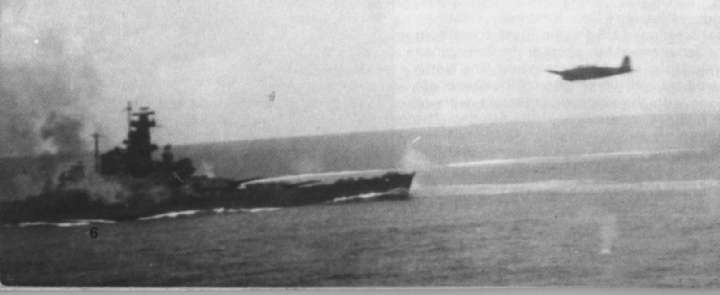

Enterprise, with South Dakota in the background, during

the attack. During this phase, Enterprise lost her forward elevator,

which she would only have repaired in January 1943.

Enterprise, with South Dakota in the background, during

the attack. During this phase, Enterprise lost her forward elevator,

which she would only have repaired in January 1943.

|

In shallow

runs forced upon them by the closing squall, several Vals were blasted

apart by the combat-experienced gunners of Enterprise and the new

but eager gun crews of South Dakota. One bomb came reasonably close

to hitting the carrier, but did not; she would stay unharmed through the

attack. Other Vals chose other targets, South Dakota and San

Juan being their most appreciated targets. Neither sustained serious

harm, although both were hit and temporarily lost their steering control.

Enterprise, her center elevator down and her forward elevator locked

involuntarily in the "Up” position, recommenced landing her planes. It

was largely due to the brilliance of Enterprise's LSO, Lt. Robin

Lindsay, waving the paddles at his station on the starboard side of the

flight deck, that 57 planes were recovered by 1500. |

Enterprise's

battle was over for good. Unable to launch planes, unable to recover more,

Kinkaid pointed her bow south and out of the action. Hornet was,

however, a different subject. The end of the attack on her had left her

burning, but by 1000, she had her fires under control, and the prospect

of regaining momentum seemed real. Rear-Admiral Murray ordered Northampton

to tow the wounded carrier to safety. The Japanese preoccupation with

Enterprise left him with sufficient breathing space for the moment.

At 1130, after brief interruption, Hornet moved with four knots

through the calm seas, 800 of her crew taken off. The tow parted at 1140,

but was restored at 1450: too late.

| Admiral

Kakuta had scraped the bottom of his plane contingent, assembling seven

B5N Kates with as many Zeros as escorts, and found the wounded carrier

at 1520. Put into a corner, unable to move, Hornet fought back with

the ferociousness of a wounded animal, but her electricity had not returned,

and all she could provide for her own defense were the 20mm guns, hand-held

and –aimed, along her starboard side. Two Kates were shot down; two pointed

themselves at Northampton; two torpedoes missed – but at 1523, one

scored within feet of the first torpedo hit that day, and finished the

carrier. Without the slightest chance of regaining her own forward

momentum, with her engine rooms wrecked and unable to escape the coming

onslaught of surface action groups surely heading for her, Admiral Murray

ordered her abandoned, a decision to which Zuikaku's last, third

strike could add little.

Murray,

aboard Pensacola, ordered destroyer Mustin to sink the derelict

carrier, which she attempted with her eight torpedoes. Hornet refused

to go under, and destroyer Anderson coming on the scene couldn't

help the process either, although she added eight more torpedoes . When

Hornet stubbornly clung to her life, both destroyers pumped five-inch

shells into her until the presence of Japanese ships suggested a swift

retirement. It was two IJN destroyers that with four Type 93 torpedoes

ended Hornet's agony at 0135 on 27 October. |

A Kate passing over Northampton, heading for Hornet.

The heavy cruiser would be sunk during the Battle of Tassafaronga in late

November 1942.

A Kate passing over Northampton, heading for Hornet.

The heavy cruiser would be sunk during the Battle of Tassafaronga in late

November 1942.

|

This ended

the Battle of Santa Cruz. Enterprise and the remnants of the Hornet

group retired toward Espiritou Santo, and the fuel-conscious Japanese,

running almost on fumes, elected not to pursue their beaten foes.

Aftermath and Results

The morning

of 27 October saw Enterprise in bad condition. Her forward elevator

was stuck in the "Up” position, no one daring to move it for fear of having

it stuck in the "Down” position. Her task force was in good condition,

but she would be severely handicapped for several weeks to come. The loss

of Hornet was a serious blow to American strategic planning.

It was

fortunate indeed that the IJN, on recovering its carrier planes, found

that it had lost the larger part of them. None of the four fighting airgroups

had enough planes left to continue operations; with the shot-down planes,

many hundreds of Japan's last highly trained aviators had perished. The

rapier that Evans and Peattie pointed the IJNAF out to be, the brittle

weapon of a range fighter, had been thrust against the hardened steel of

the USN and had shattered, leaving the IJN with but a dagger. The Imperial

Army's failure to capture Henderson Field, and the destruction of so many

fine planes and pilots, all combined to make the outcome of Santa Cruz,

thoughan immediate Japanese tactical victory, a critical strategic defeat.

The Americans were still stubbornly tied to the airfield, and Enterprise,

though reduced in capabilities, still formed a potent weapon. It would

be up to the next month to decide who had come out the victor of this engagement,

for it set the stage for the coming succession of surface battles.